What Is “Métis”

There is no consensus on who is considered Métis or a non-status Indian, nor need there be. Cultural and ethnic labels do not lend themselves to neat boundaries. ‘Métis’ can refer to the historic Métis community in Manitoba’s Red River Settlement or it can be used as a general term for anyone with mixed European and Aboriginal heritage. Some mixed-ancestry communities identify as Métis, others as Indian.

There is no one exclusive Métis People in Canada, anymore than there is no one exclusive Indian people in Canada. The Métis of eastern Canada and northern Canada are as distinct from Red River Metis as any two peoples can be. . . . As early as 1650, a distinct Métis community developed in LeHeve [sic], Nova Scotia, separate from Acadians and Micmac Indians. All Métis are aboriginal people. All have Indian ancestry.

— R. E. Gaffney, G. P. Gould and A. J. Semple, Broken Promises: The Aboriginal Constitutional Conferences (1984), at p. 62, quoted in Catherine Bell, “Who Are The Metis People in Section 35(2)?” (1991), 29 Alta. L. Rev. 351, at p. 356.

————

What Is “Afro-Métis”

Coined by Sugar Plum Croxen, “Afro-Métis” is a term that describes the genetic and cultural mixing between Canadian Blacks (particularly from Nova Scotia) and Indigenous peoples that has occurred frequently, beginning over two hundred years ago. The term was created to assert and celebrate this reality.

Why… and Why Now?

Many Black people from the Maritimes have a history in Canada that extends over two centuries and has initial periods that include enslavement. During the colonial era, Indigenous-African interactions often led to intermarriage Unfortunately, this fact has not been well documented and has frequently remained secret, even within families.

Today, in a period of trumpery and rising intolerance, it is critical that a true narrative of the journey for both Black and Indigenous peoples across this country be developed and publicized. It is in self-knowledge and public recognition of one’s identity that pride and strength can be developed and sustained. Our group has chosen to use music to spark a process of awareness, discovery and discussion, both for ourselves and for others. Why? Because we seek harmony.

————

See also http://www.metismuseum.ca/resource.php/00726

“Métis Identity“ by R. Préfontaine, Leah Dorion, Patrick Young and Sherry Farrell Racette

This excellent article informs the reader about the roots of Métis identity and how the Métis have self-identified throughout history. Readers will also be informed of current efforts by Métis leaders to foster a stronger Métis identity through self-governing institutions. The article traces the roots of Métis sense of uniqueness as a cultural group, discusses how other groups have viewed them, and presents some sources for tracing genealogy.

http://www.metismuseum.ca/media/document.php/00726.Métis%20Origins%20and%20Identity.pdf

Publisher: Gabriel Dumont Institute

Date of Copyright: May 30, 2003

Excerpts from “Métis Identity“ by R. Préfontaine, Leah Dorion, Patrick Young and Sherry Farrell Racette …

————

All the authors who contributed to the “New Peoples” Forum and Métis Legacy demonstrate that Métis identity has existed in various locales over time. For instance, Jacqueline Peterson’s excellent essay “Many Roads to Red River: Métis Genesis in the Great Lakes Region, 1680-1815”, demonstrates that various Métis communities were on the verge of proclaiming their group identity before the region was inundated by Anglo-American agrarians. Verne Dusenbury and Martha Foster each document the dispossession of the Montana Métis. John S. Long analyzes how the Métis in north-eastern Ontario were registered as Status Indians during negotiations for Treaty Nine, and Trudy Nicks and Kenneth Morgan describe how a unique Métis identity developed in Grande Cache, Alberta. Tanis Thorne’s masterful monograph, The Many Hands of My Relations, discusses the development of a mixed-blood group identity in the Lower Missouri. Leah Dorion details how her family, the Dorion’s, established mixed-blood/Métis kinship ties from Lower Canada (present-day Québec) to the Lower Missouri to the Pacific Northwest and finally to Cumberland House, in what is now Saskatchewan. Métis identity in the Pacific North West has finally been delineated by John C. Jackson and by Sylvia Van Kirk in her recent essay on Victoria, British Columbia’s founding Métis families.

————

While most cross-cultural encounters in the early years of contact and colonization were between First Nations and Europeans, others were present as well. The fact that African slavery was a part of the early history of Canada is one frequently forgotten. Slavery existed in New France and continued under British rule until an abolitionist law was passed in 1794. The law allowed slave owners to keep the slaves they had, although any children born after July 9, 1793 were freed upon reaching the age of 25. The last slave in Ontario was freed in 1820. In 1834, Britain passed a law abolishing slavery in their colonial territories. Slavery continued in lands under American jurisdiction until after the Civil War in 1865, with the exception of those northern states that had passed anti-slavery legislation. Slaves, both First Nations and African, were members of early fur trade communities, particularly in the Great Lakes region. Many of the early groups who traveled into First Nations territory for exploration or trade had one or more Africans among the party.

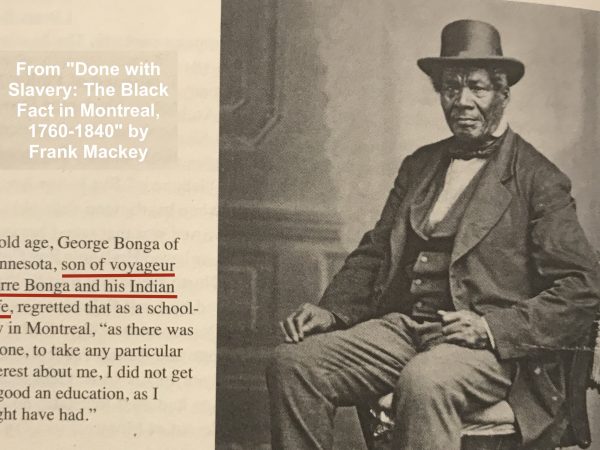

The first child born at Brandon House to Alexander Henry’s fur trade community of Nor’Westers was the daughter of Pierre Bonga and a Saulteaux woman. Pierre Bonga was born a slave and earned his freedom because of his service as the chief guide in western expeditions. His father, Jean Bonga, had been born in the West Indies and was brought to Michilimacinac in the Great Lakes by Captain Daniel Robertson who was the post’s first British commander following the fall of the French in North America in 1763. Jean Bonga and his descendants became influential members of the fur trade community.

Another man who became an important member of the emerging Métis communities in the Great Lakes was Jean Baptiste Point du Sable. Although his origins are somewhat hazy, he was an educated man of mixed ancestry from Haiti who became involved in the fur trade. He married a Potawatomi woman named Kittihawa and is recognized as the founder of the community of Eschikagou [Chicago] in 1772.

One thought on “Definitions of “Métis” and “Afro-Métis””

I am Red River Métis and And my grandfather was mixed black and native from the east coast. If you want talk more with me about my music and art as an Anglo/Afro/Métis contact me. I would love to contribute to the culture.